I'll never forget the first time I read The Outsiders.

Fourteen years old. Sprawled across my bed. The world outside my window felt impossibly big and terrifying in that way it does when you're young and everything matters so much it physically hurts. S.E. Hinton's novel about Ponyboy Curtis and his gang of Greasers didn't just speak to me—it grabbed me by the collar and shook me awake. Here were kids dealing with class warfare, violence, loss, and the desperate need to belong, all while trying to figure out who they were beneath the leather jackets and slicked-back hair.

The Outsiders turns 57 this year. And it's still relevant. Still devastating. Still necessary.

If you're anything like me, you've read Hinton's masterpiece more than once. Maybe you're searching for that same electric feeling—that perfect storm of teenage angst, found family, and social commentary that made The Outsiders so powerful. You want characters who feel real. Dialogue that crackles. Stakes that matter. Stories that don't talk down to young readers or sugarcoat the harsh realities of growing up on the wrong side of the tracks.

I've spent over a decade reading and analyzing young adult literature, and I can tell you: books that capture what Hinton accomplished are rare. But they exist. I've found them. And I'm about to share them with you, because everyone deserves to experience that gut-punch of recognition when a character's struggle mirrors your own, when a friendship on the page reminds you why loyalty matters, when a story makes you believe that maybe—just maybe—things can get better, even when the world feels determined to prove otherwise.

So here's my list. Some are classics you might've missed. Others are newer titles that understand what made The Outsiders timeless: the understanding that teenagers aren't just adults-in-waiting, but fully formed people navigating impossible circumstances with whatever tools they've been given.

Junior's story hits different. This semi-autobiographical novel follows a fourteen-year-old budding cartoonist who makes the devastating decision to leave his school on the Spokane Indian Reservation to attend an all-white high school in a nearby town. Talk about being caught between two worlds. Junior faces poverty, alcoholism, loss, and the constant feeling of not belonging anywhere—not on the reservation where he's now seen as a traitor, and certainly not at his new school where he's the only Native American student. Alexie writes with humor and heartbreak in equal measure. The illustrations (by Ellen Forney) add another layer of emotional depth, showing us Junior's interior world when words aren't enough. Like Ponyboy, Junior is trying to survive in a system that wasn't built for him, finding his identity while the world keeps trying to tell him who he should be.

Okay, hear me out on this one. It's technically an adult thriller, but the themes align perfectly with The Outsiders. Set in a small Texas town, Heaberlin's novel explores how communities create outcasts and how those outcasts band together to survive. A decade after a popular girl disappeared, a one-eyed girl is found on the side of a road, setting off a chain of events that unearths long-buried secrets. The novel examines class divisions, the way small towns protect their own (and destroy those who don't fit), and the bonds formed between people society has deemed unworthy. It's atmospheric and haunting. Dark and beautiful. The found family element is strong here, as is the exploration of how poverty and prejudice shape destinies.

Walter Dean Myers was a master at capturing the interior lives of young Black men navigating systems designed to destroy them. Monster tells the story of sixteen-year-old Steve Harmon, on trial for his alleged participation in a robbery that resulted in murder. The novel is formatted as a screenplay—Steve's way of processing and distancing himself from the nightmare his life has become. Myers doesn't give us easy answers. He makes us sit with the discomfort of a broken justice system, the way society sees young Black men as threats rather than children, and the question of identity when the world has already decided who you are. Like The Outsiders, this is a story about being judged before you've had a chance to speak, about the arbitrary nature of fate, and about maintaining your humanity when everything around you suggests you're something less.

If you loved the friendship between Ponyboy and Johnny, you'll fall hard for Aristotle and Dante. Set in El Paso in 1987, Sáenz's novel follows two Mexican-American teenagers who become unlikely friends over the course of a summer. Ari is angry, solitary, haunted by the brother in prison that his family refuses to discuss. Dante is open, artistic, unafraid to be himself. Their friendship transforms them both, helping them navigate questions of identity, sexuality, family trauma, and what it means to be truly seen by another person. The prose is lyrical without being pretentious. The emotional beats are earned. And the exploration of masculinity, particularly within Latino culture, adds layers of complexity that make this more than just a coming-of-age story—it's a meditation on how we save each other.

Thomas's debut novel became a cultural phenomenon for good reason. Sixteen-year-old Starr Carter witnesses the fatal shooting of her childhood best friend Khalil at the hands of a police officer. Suddenly she's thrust into the national spotlight, forced to navigate two worlds: the poor, predominantly Black neighborhood where she lives, and the wealthy, predominantly white prep school she attends. The code-switching, the code of the streets, the impossible choices—it's all here. Like The Outsiders, this is a book about systemic inequality, about how society pits groups against each other, about finding your voice when speaking up could cost you everything. Thomas doesn't shy away from rage. She lets Starr be angry, scared, conflicted, and brave all at once. The found family of Starr's community, the way they protect and uplift each other in the face of violence and oppression, echoes the Greasers' fierce loyalty.

If you haven't read Hinton's other work, start here. Rumble Fish is grittier than The Outsiders, more experimental in structure, more nihilistic in tone. Rusty-James idolizes his older brother, the Motorcycle Boy, a legendary former gang leader who's now... different. Changed. The novel takes place over a compressed timeline, giving it a fever-dream quality as Rusty-James tries to live up to an ideal that may never have existed. Hinton explores similar themes—gang violence, class struggle, the desperation of youth—but with a darker lens. The Motorcycle Boy is color-blind and partially deaf, disconnected from the world in ways that make him both fascinating and tragic. This is The Outsiders' older, weirder, more damaged sibling.

Two perspectives. Two teenage boys. One act of police violence that changes everything. Rashad is brutally beaten by a police officer who mistakes him for a shoplifter. Quinn witnesses the assault—and realizes the officer is the older brother of his best friend, a man who became a father figure after Quinn's own dad died in Afghanistan. Reynolds and Kiely alternate chapters between Rashad and Quinn, showing us how a single incident ripples outward, forcing everyone to choose sides. The novel examines complicity, allyship, racism, and the courage it takes to do the right thing when doing so means losing everything you know. Like The Outsiders, this is about boys becoming men in a world that's already decided their worth based on factors beyond their control.

Stay with me—I know this seems like an odd choice. The Sinclair family is old money, summer homes on a private island, the opposite of the Greasers' world. But beneath the privilege lies rot. Cadence Sinclair suffers a mysterious accident during her fifteenth summer on the island, and she can't remember what happened. As she pieces together the truth, Lockhart reveals a story about class (even among the wealthy, there are hierarchies), about the lies families tell to maintain appearances, and about a group of teenagers—the Liars—who become each other's refuge against the toxicity of their family. The twist will gut you. The themes of loyalty, sacrifice, and the cost of rebellion against an unjust system align more closely with The Outsiders than you might expect. Plus, Lockhart's prose is stunning—spare and poetic, every word earning its place.

Sixty seconds. Seven floors. One decision. Reynolds tells this entire novel in verse, following fifteen-year-old Will as he rides an elevator down from his eighth-floor apartment, his brother's gun tucked in his waistband, determined to follow The Rules: Don't cry. Don't snitch. Get revenge. On each floor, someone from Will's past gets on the elevator—people who've died, ghosts come to bear witness to his choice. The novel takes place in real time, the descent both literal and metaphorical as Will grapples with the cycle of violence that's claimed so many lives in his community. Like The Outsiders, this is about boys forced to become men too soon, about the arbitrary rules that govern life in certain neighborhoods, about the weight of loss and the seduction of revenge. Reynolds doesn't give us a tidy ending. He makes us sit with the impossibility of Will's situation, the way poverty and violence trap people in cycles they didn't create and can't escape.

Grimes gives us eighteen voices—eighteen teenagers in a Bronx high school, all finding themselves through poetry. Their English teacher starts an open mic poetry session, and suddenly these kids who've been walking past each other in the halls start really seeing each other. Each student gets their moment, their poem, their truth. There's Tyrone, trying to escape his neighborhood's expectations. Raul, dealing with abusive parents. Diondra, facing colorism. Wesley, hiding his passion for art behind a tough exterior. Like The Outsiders, this novel understands that teenagers are complex, that they contain multitudes, that the masks they wear rarely reflect who they really are. The found family here is a classroom, a temporary refuge where vulnerability is strength and everyone's story matters.

Charlie's letters to an unnamed friend chronicle his first year of high school, and they're devastating in their honesty. He's dealing with trauma, mental illness, the suicide of his best friend, and the overwhelming confusion of adolescence. When he's adopted by a group of seniors—Patrick and Sam—he finds the belonging he's been desperate for. Chbosky captures the intensity of teenage friendship, the way certain people can save your life just by seeing you. Like The Outsiders, this is about found family, about the arbitrary nature of social hierarchies, about surviving when the world feels like it's designed to break you. Charlie's vulnerability, his inability to hide his emotions behind a tough exterior, makes him a different kind of protagonist than Ponyboy, but his journey toward self-acceptance and his fierce love for his friends echo the bonds between the Greasers.

Fabiola Toussaint arrives in Detroit from Haiti on the verge of her seventeenth birthday, ready to start her new life in America with her mother. Except her mother is detained by immigration officials, leaving Fabiola alone to navigate a new country, a new school, and a new family—her three cousins, who live in a house on American Street in a neighborhood nothing like the America she'd imagined. Zoboi weaves Haitian Vodou mythology throughout the narrative as Fabiola tries to find a way to free her mother while surviving the dangerous world her cousins inhabit, where gang violence and police brutality are everyday realities. The exploration of the American Dream's dark underbelly, the way poverty and systemic racism trap families, the fierce loyalty between the cousins—it's all very much in conversation with The Outsiders' themes.

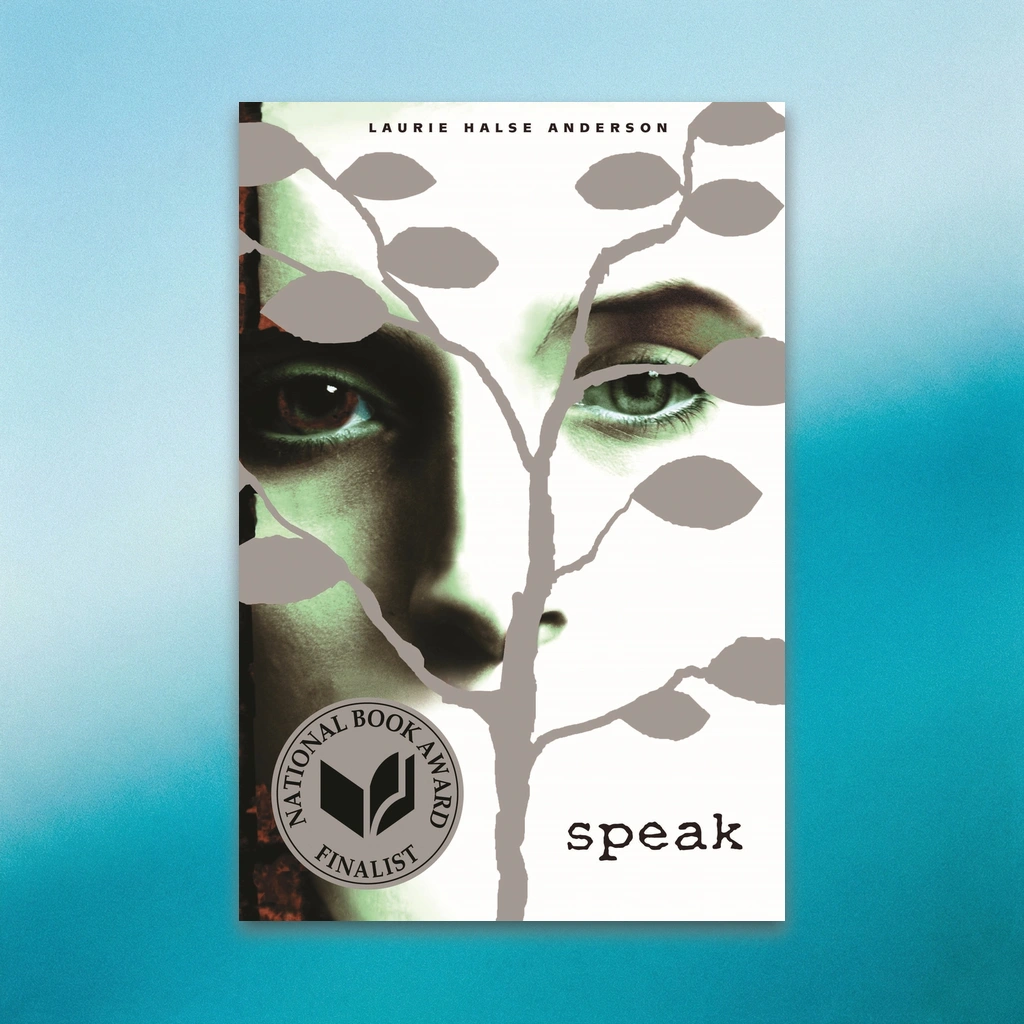

Melinda stops speaking after calling the cops on an end-of-summer party, making her the most hated person at her high school. What her classmates don't know is why she made that call—she was raped by a popular senior, and she's been carrying that trauma alone. Anderson's novel is a masterclass in voice, showing us Melinda's interior world as she struggles to find the words for what happened to her. Like The Outsiders, this is about the arbitrary cruelty of social hierarchies, about being judged without anyone knowing your story, about finding the courage to speak your truth when doing so could destroy you. The found family here is smaller—an art teacher who sees Melinda when everyone else looks away, a few friends who slowly piece together the truth—but no less important.

There they are. Thirteen books that understand what Hinton knew when she wrote The Outsiders at sixteen: that teenagers are living through real pain, real joy, real stakes. That class and race and identity matter. That found family can save your life. That the world is often unfair, but connection—real, honest, vulnerable connection—makes it bearable.

Some of the links above are affiliate links. If you purchase through them, CritiReads may earn a small commission at no additional cost to you. This helps support our work!